In 2020 The Input Party initiated a collaboration with the Institute of Social History in Amsterdam (IISG). Together with 6 participants we visited the archive, were able to go through a lot of material and take some images home. After some time we came back together in the IISG for a special edition of an Input Party where participants connected images from the archive to images from their own research. One of our participants was Alina Lupu, who went through boxes of the squatters movement in Amsterdam and was captivated by pictures of the squat De Kalenderpanden. Ignited by these images she embarked on a research that would take more than a year and would end up in an audio essay, commissioned by Ja Ja Ja Nee Nee Nee radio. On this page you can find the script of that essay, our 3rd publication in our Footnote series.

More more information about Lupu’s work please visit: https://theofficeofalinalupu.com/

A Collision with the Past.

Written and sourced by Alina Lupu

– 2021

Intro:

The Kalenderpanden is a former squat located in the East of Amsterdam. It is a building as long as a year and it takes me one year precisely – November 2020 to November 2021 – to wrap up my thoughts about it and about squatting.

In case you’re wondering “what the hell is squatting anyway?!”, allow me to make a quick parenthesis:

Historically – squatting in the Netherlands started in the 1960s. The dynamic of squatting – people in need taking over spaces unused or marked for renovation or demolition speaks about a housing shortage in the cities where it happens. But it also speaks about property speculation.

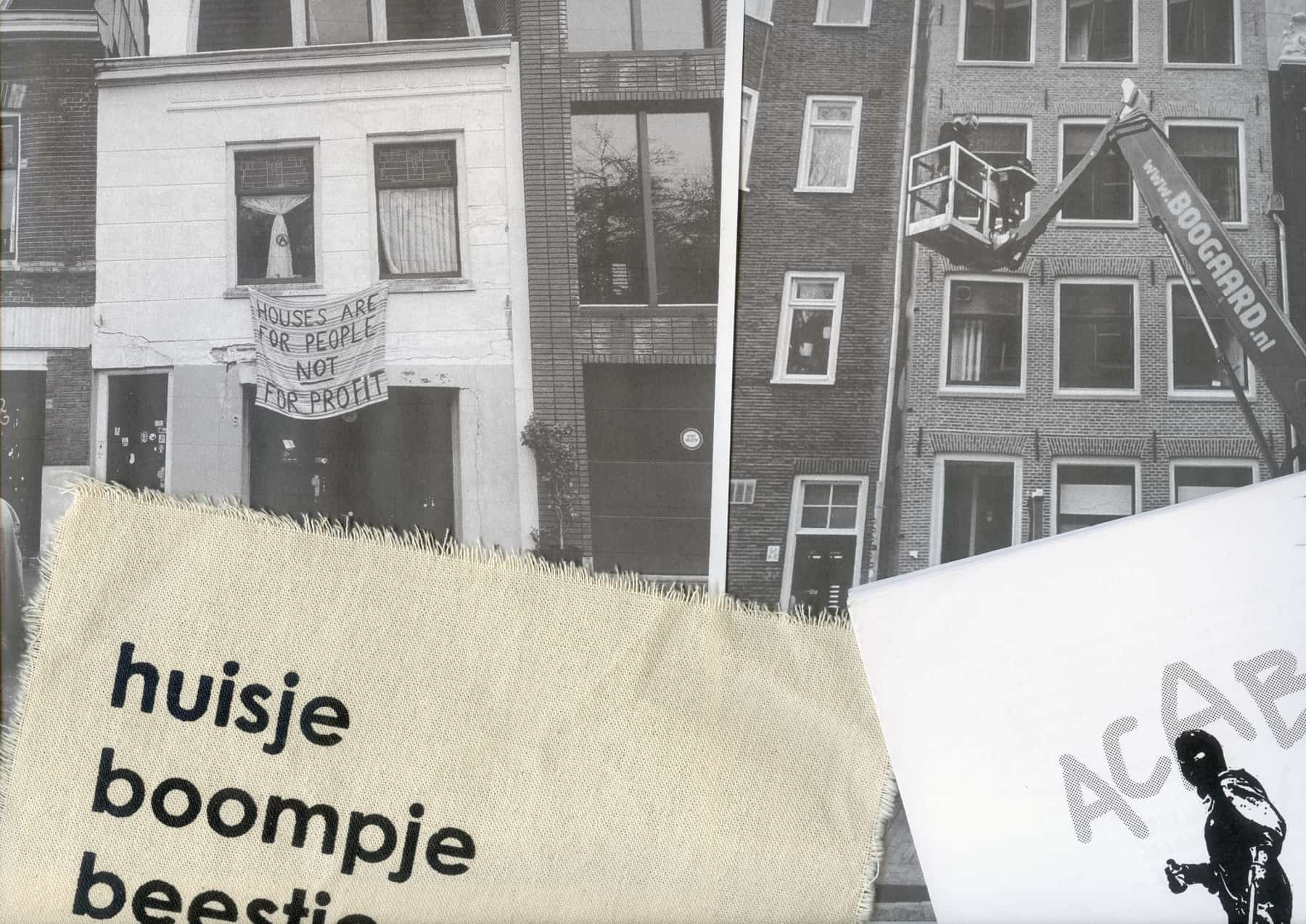

In some cases (now and in the 60’s) buildings are declared uninhabitable way before it’s necessary. They are marked for demolition and the people that live in them (usually lower income) are taken out, displaced, to make way for new property development. What squatters do in such cases is pull an alarm trigger to signal to property speculation.

The overall market at the moment is fucked. With prices rising in the last two decades in Amsterdam from an average of 200.000 Euros for an apartment to the same apartment being valued at half a million. At the same time, squatting is generally, at least for a brief moment – while someone breaks in – an illegal affair.

In the past, the municipalities took a less proactive approach to evicting squatters. Some even passed on the building to the ones that broke in. In some cases squatters had a hand in negotiations – they might have been offered alternative buildings to live in, somewhere further from the city center, for example. And then they could take them or not. Gradually though, since the end of the ‘80s, the story changed, eviction notices got shorter and more violent.

The 2010 nationwide Dutch squatting ban criminalized squatting and derailed the once-thriving anarchist direct action movement that demanded equal rights to housing. Then, in 2021, the time that squatters are evicted decreased in Amsterdam to 72 hours from the moment the building was taken over.

There is also a construction that was invented to work against squatting. This construction is the so-called legal alternative and it’s named anti-squat. Anti-squat functions through temporary contracts (with eviction times of 1-3 months – 3 months is luxurious!) and with no guarantee of a new place once one gets evicted. The contracts give few rights to tenants, they are in buildings which are not renovated, sometimes with no running water, or heating, they also are aimed at individuals, not at families, leading to situations in which if one has a child while in anti-squat they can get evicted.

The companies that offer anti-squat contracts are specialized service contractors like AdHoc, VPS, but also the housing companies themselves but also Ymere, Rochdale, Eigen Haard… etc. The rent is low, but in fact there shouldn’t be any rent at all since what you’re basically becoming if you take on an anti-squat contract is an unpaid guard for a space that will eventually be redeveloped for someone that earns much more than you do.

Who takes this sort of contracts?

Well, artists need housing and exhibition space for cheap. They also need to not get in trouble with the law. As a result, a LOT of them currently live anti-squat in larger Dutch cities.

Back to the present!

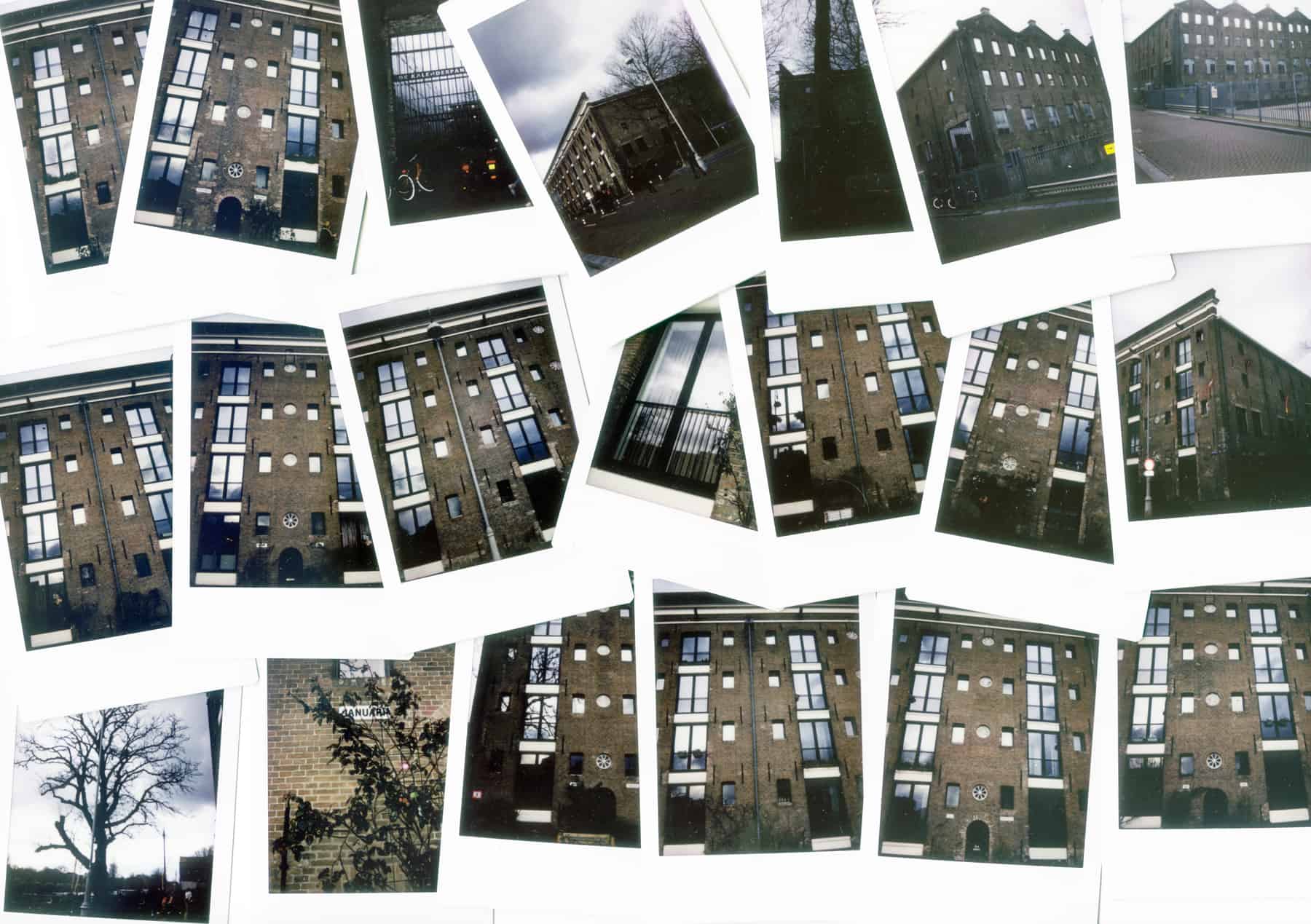

The building – a large warehouse with an exposed brick exterior, overlooks a canal, in a relatively quiet, residential area, behind a zoo, next to a basketball court, and close to the constant hum of an energy grid provider. Its peppered with windows, both wide and narrow and it goes from January on one side, all the way to December on the other. The months are each marked above the ground floor individual entrances into people’s homes, from left to right. Nothing really brings to mind its history as a squat. While walking by it one might naturally think of its history as a storage space repurposed since it has an interior courtyard, impossible to access unless you live there, which seems to have been carved into half of the building. The outer shell of the Kalenderpanden therefore still exists in the back of the building, but it’s only left as a means to preserve its looks, having lost its function during the re-modeling. It’s crystal clear though that it wasn’t initially built with living in mind, but the traces of its history between 1996 and 2000 are all but lost, unless one digs into looking for it online, since it existed at that sweet spot when online presence was on the rise and therefore its archive is extensive.

Throughout the past year I’ve worked on figuring out just what attracted me to the place, and as I was thinking through this I’ve also witnessed the resurgence of squatting as a housing practice in Amsterdam.

I’ll move through it month by month:

November

(24th, 1996 The Kalenderpanden on the Amsterdam Entrepotdok are squatted. They are owned by the Municipality of Amsterdam/Municipal Land Company. The complex consists of twelve warehouses bearing the names of the months)

December to January

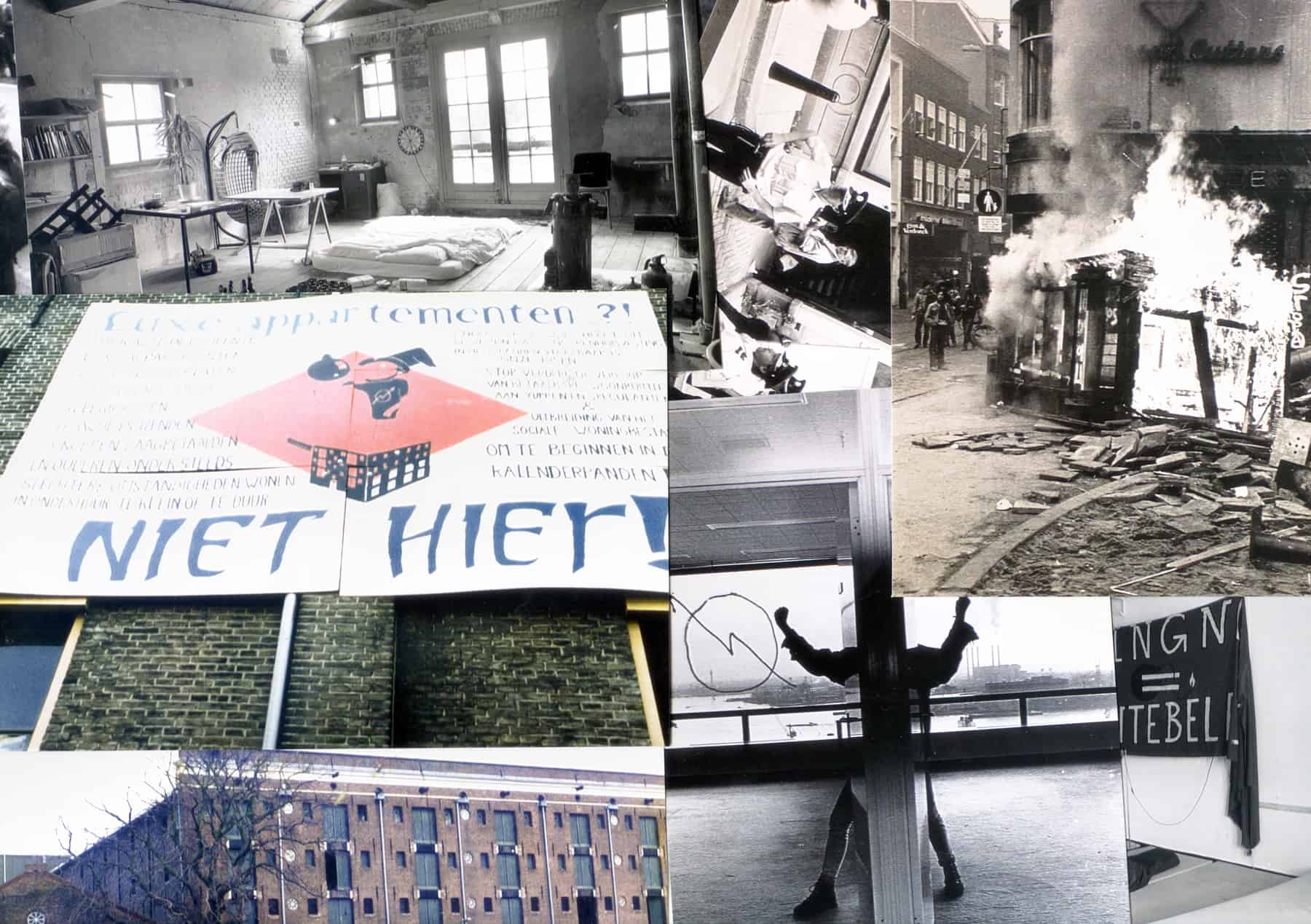

(In the harsh winter of ’96 / ’97 there is only one wood- burning stove and many broken windows. The property is populated by a large pigeon colony. There is a thick layer of pigeon shit and cadavers everywhere. No water, electricity and no gas. The pigeon shit is removed, rooms are divided, electricity lines are installed, etc.)

February

(present day) There are two separate ways to enter the Kalenderpanden. One is on the Entrepotdok and the other one turns a bend, on Geschutswerf.

I watch, on one of my outings, a group of 5 friends walking by that stop in front of the month of June and looking up towards a folded “For sale” sign from Kuijs Reinder Kakes Real Estate developers.

The 5 friends drop a pin, check the address they’re at and look for the listing online. As if on cue they let out a collective sigh. I mimic their reaction when I stumble across the same listing, Geschutswerf 23.

It reads like you’d like it to read if you were to drop a cool

€ 1.050.000 on property.

“A unique loft apartment of 155 m², spatially divided, and with a depth of 30 meters. Situated in the beautiful Plantagebuurt on a car-free road with a view of the water of the Entrepotdok and Artis zoo. The apartment is located on the first floor in a beautiful historic warehouse, originally built in 1840. In 2001, the building was renovated by the renowned architects Claus & Kaan with a lot of craftsmanship and an eye for detail into the exclusive apartment complex ‘De Kalendarpanden’. It is not without reason that the historic building has been given the status of a national monument. Perhaps the most special is the view of a wooded hill of Artis where the Algazelles graze daily.

All the conveniences of the city are within easy reach.”

Depending on your status, depending on the time that passed, you might perceive the distance from the city center as either convenient, or an offense.

Convenient for a millionaire, an offense if you’re a squatter.

In the ‘80s, the area of the Kalenderpanden was offered as an alternative to squatters which the municipality wanted to evict from the historical center – think 17th century mansions, but also the Jordaan. In 2000, the squatters of the Kalenderpanden were asked to move to Zeeburger Eiland, that’s double the distance from the historical center of Amsterdam. From the middle of the action, to 3km away, to then 6 km away

Since then squatters have been gradually removed only weeks into their occupation, without any offers or a chance to combat the removal.

March

(1997 Suddenly the Public Prosecution Service wants to proceed with eviction due to local peace breaking. The squatted part would be connected the non-squatted part that is in use by the tenant. The squatters file a lawsuit against this and win after a visit by judge R. Orobio de Castro to the building.

The Municipal Ground Company refuses permission to connect water. Fetching water every day from a gas station or a neighboring squat. Flushing water for toilets is pumped from the canal. After submitting the address to the city council, the owner changes tactic.

Early March 2000 The ground floor and part of the first floor are squatted. Apart from some corners, all six warehouses have now been squatted and the day café has a south-facing terrace.)

—

(March, present day) 2021 The squat-anti-squat dynamic, by now ubiquitous, can be seen in the case of the Anarcha- Feminist Group Amsterdam and those that took their place.

The building they squatted at Spuistraat 59, in Amsterdam on March the 8th, 2021, was evicted violently by the police a few weeks in. The building was smack dab in the middle of the city center, but also significantly on a street which had undergone massive gentrification and squat evictions in the past couple of years, therefore a symbol in itself. This building was then given over to the VPS property speculators and offered as an anti-squat contract to two artists that organize exhibitions as a “nomadic gallery”. The nomadic space displayed young freshly graduated artists, it was funded by the Amsterdam Fond voor de Kunst, it had a semi-professional social media presence, and in one elegant move, it managed to erase the history of the squatting action which preceded it.

I found the very impersonal reply from the artist exhibiting in the nomadic gallery as an interesting take on how to deal with ones ethical standing as an artist. In short: sound humble, talk in general terms, deflect. I found the space organizer’s simple repost of the statement, and both of their reshares as stories on social media as further proof of their level of care.

A short dissection:

“Recently, there have been questions raised about the purpose of my window installation at Spuistraat 59.“

To which I ask: What were the questions? Where did they come from?

“The building at Spuistraat 59, which has been formerly squatted.”

Who was it squatted by? Have you reached out to the people involved? Do you know who they are?

“I wholeheartedly support the causes that the previous residents pursue.”

How?

“I will however use this opportunity to reflect on who is accountable for the shortage of affordable housing and the eviction of marginalized groups.”

I think this pretty much gets an answer in the next few lines. The struggle brings all of the parties listed together: the artist, the exhibition space, the building owner, the future residents.

“This is part of a broader conversation of (art) gentrification that is more needed than ever.”

Yup! Only… who’s going to have it if the artist and exhibition space, the ones that are actively involved in it, do not step to the table to discuss it with the other parties involved and to even realise their own involvement in it?

If in the 1960’s and 1980’s, and even in the early oughts, artists were the squatters, in the 2020’s artists end up being more often than not the complicit tools of property speculators.

But they don’t have to!

As David Graeber mentions:

“The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and we could just as easily make differently.”

I’m wondering what would have happened if instead of drafting this long statement the heads of the nomadic space would have simply handed over the keys to the Anarcha Feminist group instead.

–

(March, present day, again) My mind turned back to the description of the apartment from the Kalenderpanden and I get fixated on the algazelles. So I look up the species.

The Algazelle, which also goes by Scimitar oryx is a species of Oryx that was once widespread across North Africa.

Conservation status: Extinct in the wild, gradually being reintroduced since the year 2000.

As I think of them I’m reminded of another brief encounter that took place as I was scouting the Kalenderpanden. I started photographing the building from all available outside angles and as I lifted my lens towards the roof, on Geschutswerf a gentleman approached me – must have been in his 50s – and started to tell me that he used to go there 10 years ago when it was a squat, that he still vividly remembers the parties – the music, the smoke, the noise, the people. We fell briefly in conversation and he expressed his sadness that the place was evicted while I ended up dumbfounded that the history of the squat still lived in someone, was still walking by me, after the building itself showed no obvious trace of those 4 years of its existence.

The guy’s memory was so vivid in fact that what had happened 20 years ago feels like it was only 10.

April

(23rd 1997 – The municipality refuses to register residents in the population register.)

(April, present day)

In a rather futile attempt to access the insides of the Kalenderpanden I write an open letter to its current residents and print it in a couple hundred copies. I make my way to the building. I slide each invitation for contact into the mailboxes of the residents at both Entrepotdok and Geschutswerf. It’s a hopeless pursuit, but it makes me feel a little bit more grounded, for the first time since diving into the place’s history.

It’s also the first time that I peruse the names of the current residents, and one in particular catches my attention. A name which is also held by a local billionaire – no initials, no first name listed -, a name entangled with arts funding.

Which reminds me again of the many trials and tribulations that artists go through in order to establish a practice – those that don’t mind where their money is coming from, and those that do.

I trace back the familiarity of that name to a recently published article and I skim through it:

“Another well-known philanthropist in the Dutch art world is billionaire Rob Defares. His affinity for contemporary art is apparent in his great donations and personal involvement in various institutions. Defares is co-founder and managing director of technology-driven proprietary trading firm International Marketmakers Combination (IMC), which is specialised in high-frequency trading. (…) Defares carries out philanthropic activities through the Hartwig Medical Foundation and the Hartwig Foundation, which is also a patron of the Stedelijk Museum Fund. In 2020, the Hartwig Art Foundation was added, to which Defares donated €10 million. (…)

The money that the Hartwig Art Foundation invests in young artists thus indirectly comes from high-frequency trading, or flash trading. (…) Flash trading is also associated with flash crashes, such as the one in 2010. (…) Flash traders keep their shares for a very short time and do not aim to actually invest in the performance of certain companies and sectors, but rather to gain margins on as many small, random trades as possible – with big profits as the sole goal. Flash trading thus extracts economic value from society and privatizes invested capital from public funds, the argument goes. The more rigorous critics argue that the extractive practices of such data technology go so far as to reflect processes of primitive accumulation (predatory capitalism) that take place when capitalism colonizes new domains.”

It’s probably some other Defares though. Who’s to tell?

May

I start fussing around the house and rearranging my paperwork. Among the many work references, a copy of the Amsterdam housing survey 2021. A way to project the future expectations about living in the city of Amsterdam, via the goodwill of its residents. And for me, twelve pages of gleefully thinking about my bright housing future, of not quite understanding how my experience will shape city policy in the years to come.

I’m warned:

“Before you start…

There are no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answers. If you are unsure about the answer to a question, please provide the answer that best suits your needs.“

And I allow myself to fall down the rabbit hole of my housing history, by now counting 9 years of being an Amsterdammer:

“Since what year do you live in your present house?”

2018

“Where did you live before you moved into your current house?”

In the same city, another neighborhood – I was pushed out.

“What was your previous housing situation?”

Self-contained rented accommodation from housing association. it was an anti-squat construction.

“The following questions concern your previous house.

If you rented, what amount did you pay for renting this property to your landlord (total amount including service costs)?”

I cannot remember

“What kind of property did you have?”

Ground-floor flat

“What was the reason for moving to your present accommodation?”

The rolling tide of gentrification.

“Are you renting your current accommodation or are you its owner?”

I am paying rent.

“From whom are you renting your living space/accommodation?”

A housing corporation.

“What type of tenancy agreement/arrangement do you have?”

Tenancy agreement of unlimited duration for the entire dwelling (a normal contract). But, funny story there! In order for me to get a full-time unlimited contract, one of those things that you end up signing per year and then you extend from year to year, with a 2% increase in cost, adjusted (to inflation?), the housing corporation from which I’m renting and which was in charge of my anti-squat predicament, had to forget about me as a tenant and continue their renovations to the point where they one day knocked on my kitchen window and asked to demolish my balcony while I was still living on the property. Later that day I called them, as the bulldozer ate away at other parts of the inner courtyard, and they apologized for the confusion and sent a courier to my place with an eviction notice active immediately, but also, given their bureaucratic slip-up, their need to indeed demolish my balcony within 2 weeks time, this gave me enough leverage to negotiate a better contract for a new home. Imagine, being just a number in a system, being forgotten, falling through the cracks. And in that fall gaining the upper hand. In fact, without that fall, you’d end up being nothing.

—

It went on and on and by looking at the questions and the way they’re defined, by progressing through it, I got a glimpse into an image of the future of the city and, most strikingly, who it’s meant to be open to, who it’s meant to be hosting: the old, the young, the nuclear families, the ones that need parking, the ones that think about investing into renovating and greening up their property, in order to insure their 4+ children will get to live in a better tomorrow, the ones that worry about crime rates, and proximity to amenities, the ones that think in square meters, and might say hello to their neighbors, but that’s never implied. The picture painted is that of a functional city, one in which we’re all equal, only that couldn’t be further from the truth.

I wish I could afford to live there.

June – August

(2000 A representative survey conducted by the O + S office on behalf of the Amsterdam Anders / De Groenen faction shows that a majority of Amsterdammers are against the eviction of the Kalenderpanden:

Do you agree with the municipality’s intention to vacate the Kalenderpanden in order to build luxury apartments?

yes 28%

no 49%

don’t know or no opinion 23%

August 22nd, 2000 The eviction notice is served. This means that the building can be evacuated from October 2nd, 2000.

The sale has started through Boer Hartog Hooft, the broker of the Kalenderpanden.

The cheapest apartment is now 890,000 guilders)

September

A wall on the Kalenderpanden squat in the autumn of 2000, mere weeks before the planned eviction, boasted a quote by the Spanish anarchist Buenaventura Durruti. It went a little something like this:

“We are not in the least afraid of ruins. We are going to inherit the Earth. The bourgeoisie may blast and ruin their world before they leave the stage of history. But we carry a new world in our hearts.”

I feed the quote into Google, curious about its further ramifications, and find out that the quote is actually incomplete. The bit missing is its intro: “It is we [the workers] who built these palaces and cities, here in Spain and in America and everywhere. We, the workers. We can build others to take their place. And better ones!”

Who were the workers of 2000?

In a way, I find the omission fitting. In between 1936, when the quote originated, and 2000, the fight over space in Amsterdam continued, but the fight in question gradually shifted between the workers as actual builders, the traditional working class, towards the service workers, the young creatives, and the bourgeoisie.

Morals changed, professions shifted, and maybe so did the spirit of solidarity. The boundaries turned ever more fluid, and the new people taking up the squatting fight didn’t quite see themselves as the working class anymore. Just as the working class didn’t see themselves as squatters. In this loose space between the two, it’s the ones that could afford 155m2 lofts near the center that profited.

October

(27th, 2000 No replacement space available for the squatters.

31st, 2000 Eviction)

The Kalenderpanden eviction video is easy enough to find online.

One morning in October I wake up before sunrise, groggy, make my way to the building itself, and position myself on Geschutswerf. I slide open my iPad, search for the video, the early morning wind howling as I try to stabilize my camera and catch within the frame both the Kalenderpanden and the eviction video that’s playing, all 8 minutes of it, compressing 5 hours of struggle.

The algazelles watch me from a distance.

Playing the video in the space feels like an exorcism.

01:00AM After the Manifestation, approximately 300 people start barricading the access roads to the Kalenderpanden. The bridges on the Hoogte Kadijk and at the Entrepotdok will be raised and barricaded. ‘Spanish horsemen’ and about fifty large steel structures will be placed on the Hoogte Kadijk near the building. The asphalt is broken up with jackhammers. A trench is also dug with an excavator. The police come to take a look, but do not intervene.

05:05AM The riot police (with a water cannon) starts to intervene at the barricades on the Hoogte Kadijk, from the side of the Sarphatistraat. This is responded to by throwing stones. There are 150 to 200 people inside the barricades.

The ME shoots heavily with tear gas, and badly with the water cannon at the first barricade (near Sarphatistraat).

06:00AM The riot police comes to a halt under a rain of stones at the still growing and burning barricade on the Hoogte Kadijk.

06:45AM The water cannon is empty and is withdrawn for refueling. The gas is also gone. The traffic scanner shows that the riot police is getting anxious.

07:08AM All possible escape routes are closed by detention units.

07:15AM At the building, flares are fired.

07:25AM At the large burning barricade, the riot police gets to work with a shovel. A second shovel is on its way.

07:33AM The Bravo-00 (the general commander on site) is disabled. There are reports of 3 injured riot police.

07:42AM Two platoons are ordered to charge from the Kruithuisstraat at the Oostenburgergracht, towards the building, over the barricades. A total of 160 tear gas grenades were fired and 60 grenades were thrown between 05:15 and 07:30.

07:50AM A number of riot police threaten to approach the building via the swing bridge.

07:50AM A group of squatters and sympathizers exit the barricades at the Entrepotdok, chased by undercover arrest units. Three arrests at the Entrepotdok.

08:00AM – 08:30AM A considerable group gets away. 09:15AM The riot police enters the building.

A piece in the newspaper Trouw from the time briefly documents the eviction:

“When the sun is up, it is already over. Police officers with gas masks guard the entrances to what was a sanctuary for alternatives: the Amsterdam Kalenderpanden, next to the Artis Zoo. The streets are littered with smoking or burning debris, broken pavement tiles, scaffolding pipes and nuts and bolts, which were thrown from the building to the police in the early morning. Fifteen officers were injured (four left with bruises), police arrested 18 squatters.”

November, 2021

(present day) Perhaps the trick worked! Or at the very least it couldn’t have hurt, my little bit of exorcism.

In a piece entitled “We Have the Matches: On the Resurgence of the Housing Struggle in the Netherlands” on itsgoingdown.org I read the following:

“In the past month, two large housing protests have happened: first on September 12 in Amsterdam, with roughly 15,000 people attending, and then one October 17 in Rotterdam which was attended by almost 10,000 people. It is notable that these protests, initiated by a broad coalition of leftist and grassroots groups, were very outspokenly supportive of squatting.

The piece goes on, it turns a bend, it brings me back to the algazelles:

“as the march approached its endpoint a small group split off the demonstration with the intent to squat a house. They were instantly met with massive amounts of police who used some of the most relentless violence we have witnessed in a long time. More than 60 people got arrested and severely beaten up.”

“On October 16, an annual protest in Amsterdam was held in defense of autonomous cultural spaces. During this protest a massive building in the very centre of Amsterdam was squatted and dubbed “Hotel Mokum.”

Another piece, this time from Vice, about Hotel Mokum itself, reminds me of the gentleman that remembered the Kalenderpanden and folded 20 years of past time into 10:

“Several groups have come together to take Mokum back, both seasoned squatters and young people, for whom this was the first squat. Lisa: ‘We have been preparing for at least two months. But the idea has been around for much longer. For the younger people in our movement it has been a dream for years to be able to squat something in the city.'”

Some of the new squatters were most likely not even born when the Kalenderpanden was squatted. They can’t remember it, but they have the energy to make it anew.

Pushed to the brink of housing instability, they and other categories of people like them joined the housing protests and became unlikely forces holding hands across the divide:

“Despite not universally having a background in radical politics, all of the organizers of these protests have refused to accept the divisive narrative of the state. They have stood in clear and open solidarity with the victims of police violence and stated explicit support for squatting as a legitimized method of protesting the housing crisis.”

By mid-November 2021 Hotel Mokum gets another companion building, a new squat, this time on Ringdijk 8, in Amsterdam East. The culprits: the Anarcha-Fem group, and they do it on the precise 1 month anniversary of Hotel Mokum, as if to bind their link.

—

We’ve gone through all of the year’s months, but the year ends with questions:

For how long?

And in which direction will these actions go?

Epilogue:

On November 27th,

at around midday,

using a disproportionate amount of violence,

the Amsterdam police and the Mobile Unit,

evicted the squatters of Hotel Mokum.

6 floors,

6 weeks,

left empty.

Colophon:

This (audio) essay was commissioned by Radna Rumping of Radio JaJaJaNeeNeeNee, Amsterdam;

and inspired by Rachel Sellem and Elki Boerdam, creators of the Input Party.

Additional Voices:

Ana-Maria Guşu, Jörn Nettingsmeier, Timo Demollin, Jelle Baars.

Recording and Sound design:

Jörn Nettingsmeier.

Music by:

De 4 touze matroze; DJ Lulu;

Kuijs Reinder Kakes Makelaardij Hypotheken Verzekeringen and

Euronext Amsterdam, formerly The Amsterdam Stock Exchange.

With material from:

entrepotdok.squat.net; funda.nl/koop/amsterdam; Youtube user “vriijepiijptv”;

Retort #24 The Philanthropy Trap, by Timo Demollin;

and a recent housing survey of the Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek department of the City of Amsterdam;

and news outlets itsgoingdown.org; Vice.com/NL; and Trouw.